You bought a token. But did you buy the building?

Fractional ownership has become one of the most frequently used terms in real estate tokenization. It sounds intuitive, modern, and accessible. Yet in practice, it often creates confusion about what is actually owned, where ownership legally exists, and what a token truly represents.

This article explains, clearly and without marketing shortcuts, how most fractional real estate tokenization models work — and why we at ATEG Capital FlexCo deliberately chose a different, cleaner approach.

Legal reality comes first

In most European jurisdictions, including Austria, real estate ownership follows a strict and well-defined rule:

Ownership exists only through registration in the official land registry.

To be legally recognized as the owner of a property, a person or company must:

- sign a notarized purchase agreement

- pay real estate transfer taxes

- cover court and registration fees

- be formally entered into the land registry

If a name does not appear in the land registry, that party is not the legal owner.

Tokens, blockchain records, or platform dashboards do not replace this legal process.If a name does not appear in the land registry, that party is not the legal owner.

What fractional ownership platforms actually do

In the vast majority of real estate tokenization projects, the structure looks like this:

- A company or special purpose vehicle acquires a property.

- That company is registered as the sole owner in the land registry.

- Investors purchase tokens via a digital platform.

The tokens do not alter the land registry.

As a result, the property belongs legally and fully to the company.

Tokenholders are not registered owners of the real estate.

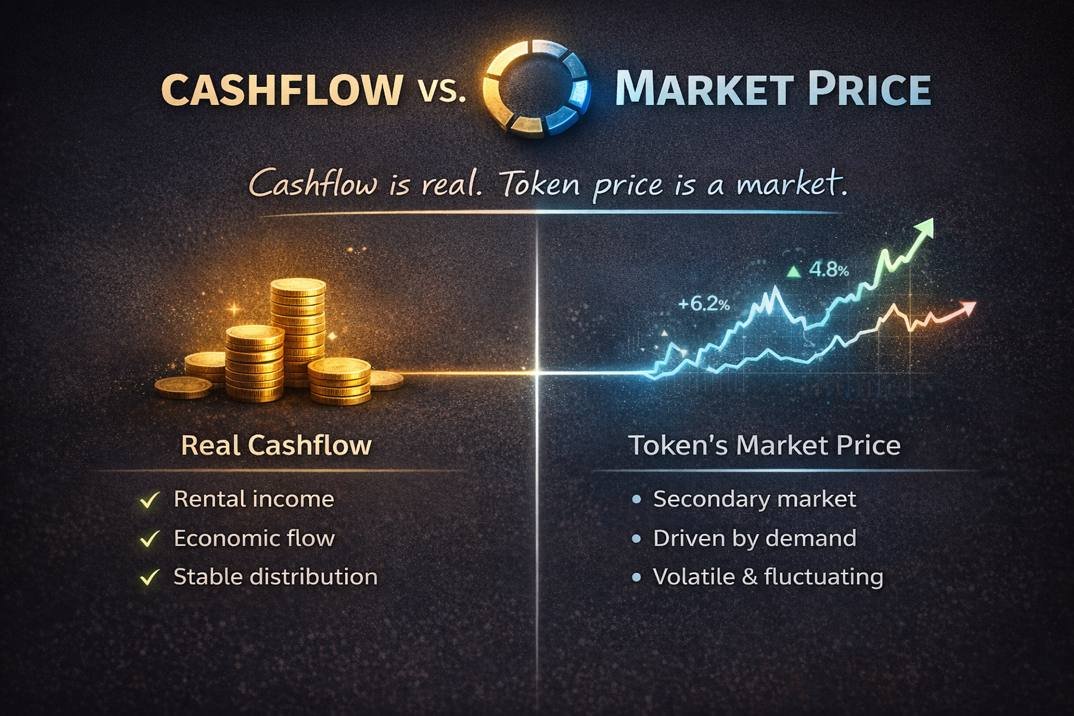

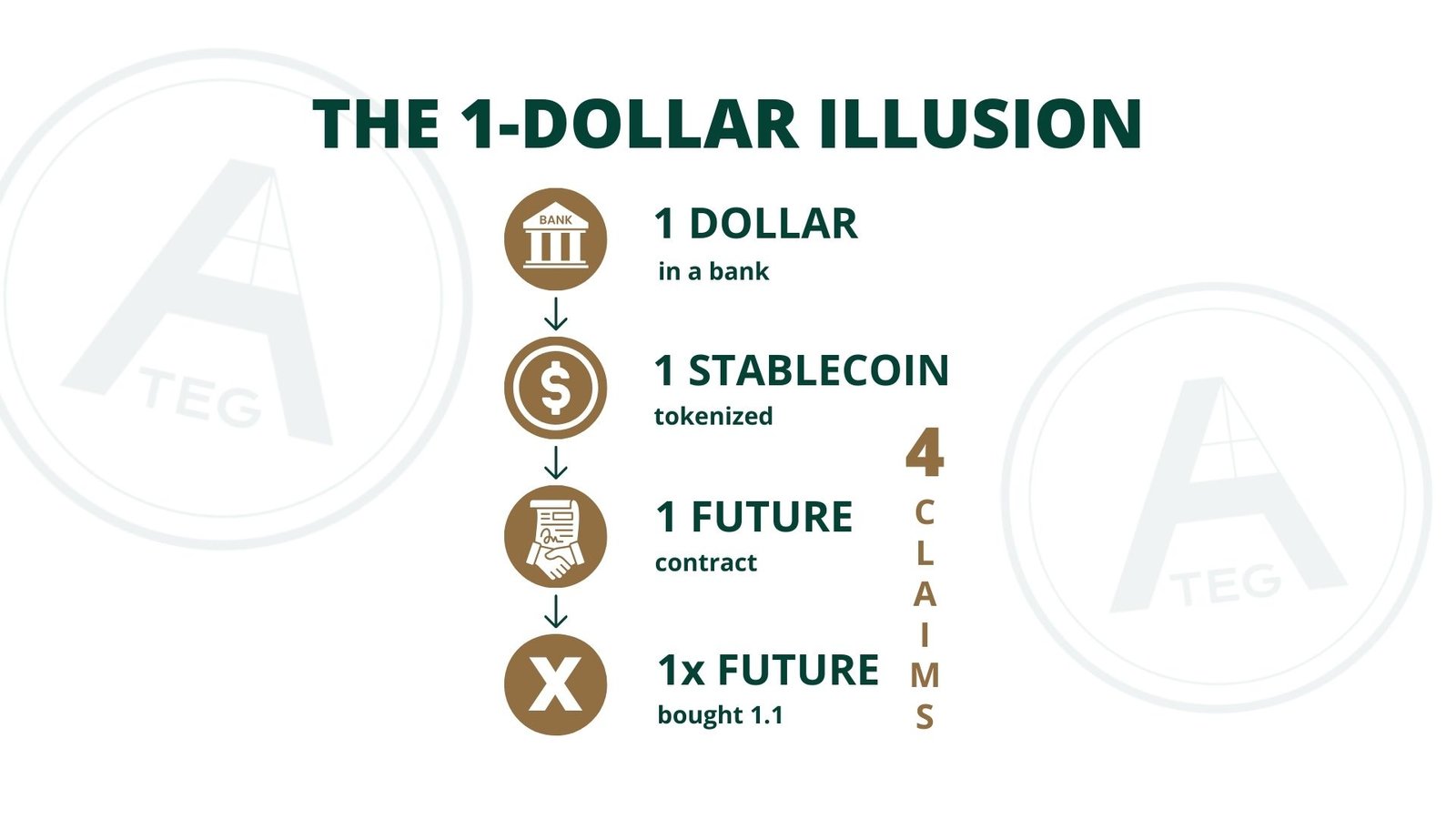

What tokenholders really hold

Instead of property ownership, tokenholders typically receive:

- contractual rights

- economic participation

- claims defined by token terms and platform agreements

These rights may include:

- participation in rental income

- participation in profits or exit proceeds

- exposure to the economic performance of the underlying asset

What they do not include:

- direct ownership of the property

- land registry rights

- independent control over the real estate

From a legal perspective, tokenholders hold claims against a company — not ownership of a building.

Why true fractional ownership is impractical

Imagine a single apartment with hundreds or thousands of tokenholders, trading tokens daily.

True ownership would require:

- constant updates to the land registry

- notarization for every transfer

- recurring taxes and fees

- legal processing for each transaction

Such a system would be slow, expensive, and unworkable.

This is why fractional ownership in tokenized real estate is almost always economic, not legal.

Why the word “ownership” is still used

- Ownership feels tangible.

- Participation feels abstract.

As a result, many platforms simplify their language to make complex structures more accessible. This is not automatically illegitimate, but it requires clarity. Long-term trust depends on understanding precisely what a token represents — and what it does not.

Why our approach is intentionally different

At ATEG Capital FlexCo, we deliberately chose not to imitate property ownership through tokens.

Not because fractional models are inherently wrong, but because blending legal ownership with economic participation often creates expectations that cannot be fulfilled in reality.

Our model starts from a clear separation.

Real assets stay where the law recognizes them

Real estate and energy assets remain owned by the operating company.

Ownership is:

- legally registered

- transparently held on the balance sheet

- governed by established property and corporate law

There is no artificial fragmentation of property titles and no implied promise of land registry rights through tokens.

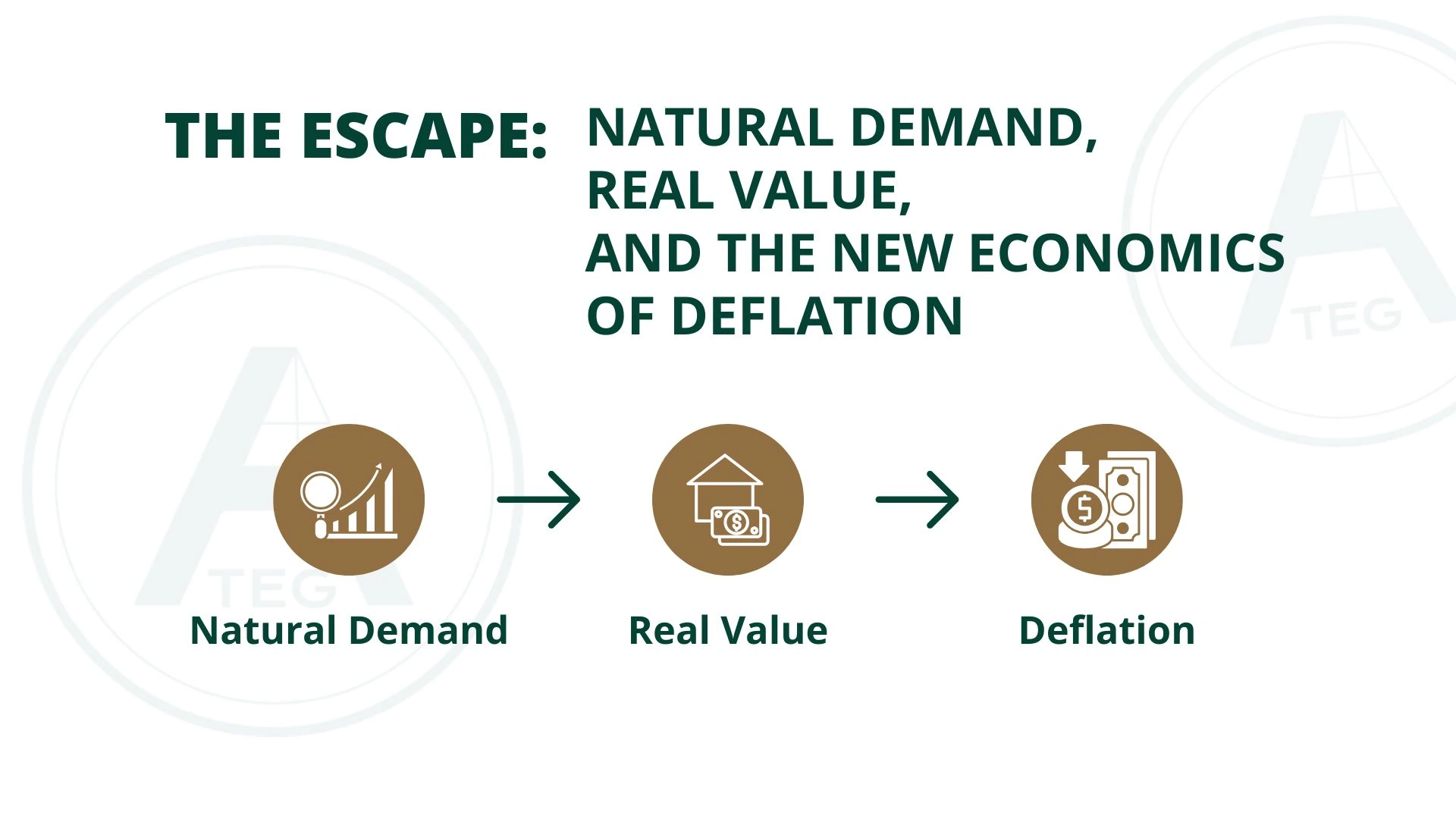

The token operates on the economic layer

The token in our ecosystem is not designed to represent direct property ownership.

It is designed to interact with real economic activity by:

- linking to operational revenues

- reflecting business performance over time

- aligning supply dynamics with real-world cash flows

This includes mechanisms such as:

- balance-sheet-based revenue logic

- supply-side deflation through burn and freeze

- alignment with monthly economic cycles rather than short-term market noise

The result is economic exposure without legal misrepresentation.

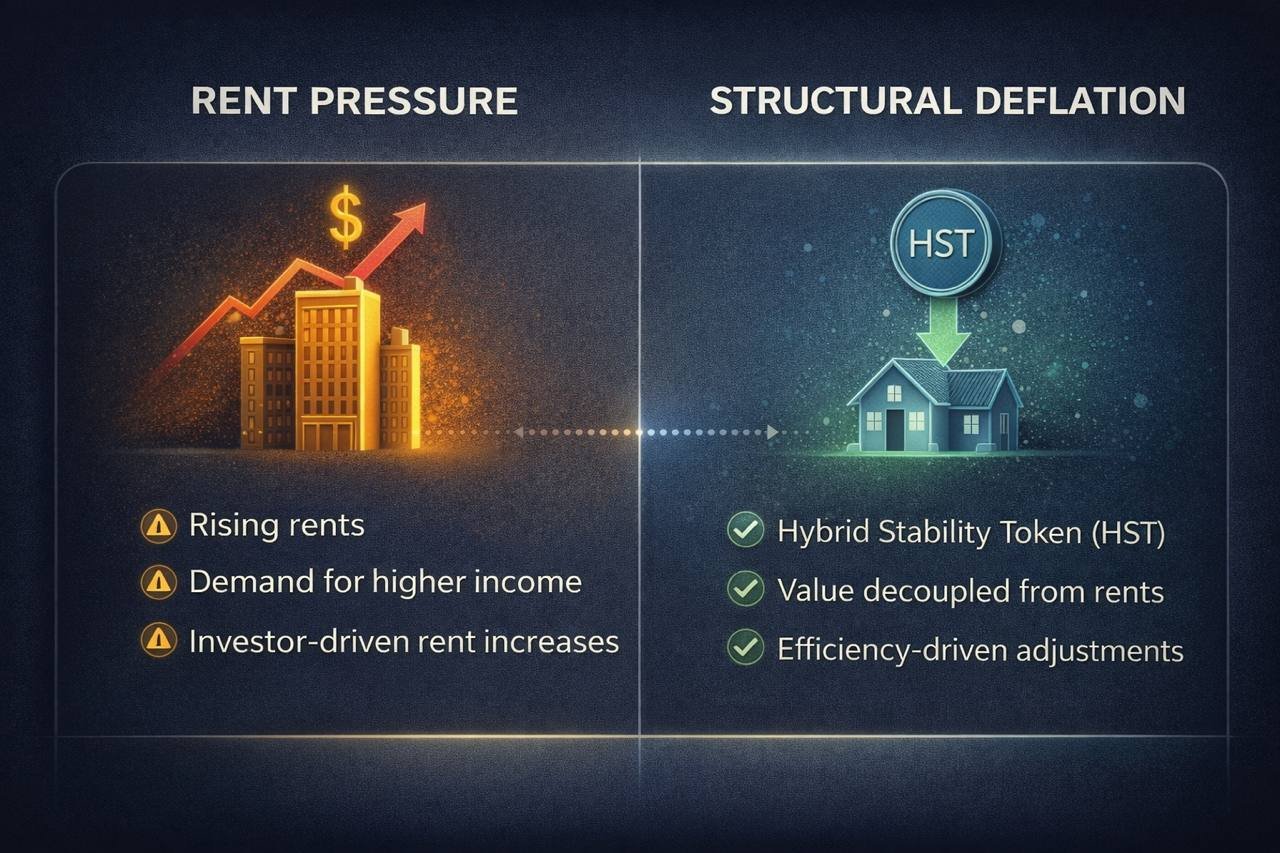

Why this structure matters long term

By clearly separating ownership from participation, three key benefits emerge:

Clarity

Participants understand exactly what they are involved in — and what they are not owning.

Regulatory robustness

The structure aligns with existing legal frameworks instead of relying on semantic shortcuts.

Sustainability

Value is anchored in real operations, not in perceived ownership narratives.

This avoids the structural tension that arises when legal reality and marketing language diverge.

A different philosophy

Many tokenization models ask:

How can ownership feel more accessible?

Our question is different:

How can digital participation be aligned with real-world economics — without pretending it is something else?

We believe long-term trust is built through transparency, consistency, and respect for legal reality.

🧩Final perspective

In most fractional real estate tokenization models, the property is owned by the company listed in the land registry.

Tokenholders do not own the building itself.

They hold economic or contractual rights — nothing more, nothing less.

Real estate tokenization does not need illusions to work.

It needs clarity about where ownership ends and where participation begins.

That distinction is not a weakness.

It is the foundation of a model designed to last.